Cartier - From High Jewellery to Horology

With 173 years spent in the pursuit of perfection, Cartier commands one of the greatest watches and jewellery dynasties. Few brands can lay claim to so many original and iconic designs. King Edward VII coined the phrase “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers” in reference to Cartier’s quality of craftsmanship and clientele. European, Russian and Indian royalty, American tycoons, Hollywood A-listers and current celebrities. The list of well-to-do clients far too voluminous to be accurately reproduced here. The evolution of the brand (to global status) spans three generations. Yet, really, it’s the story of three brothers.

Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier. The first, a visionary aestheticist. The second a pioneering entrepreneur, And the third a well-studied specialist of precious stones. Together they realised a dream of establishing the company internationally. Their reign over the first four decades of the 20th Century produced some of the best high jewellery ever seen. Born out of and directly influenced by this period came the first wristwatch for men and the emergence of a new form of horology. Combining its jewellery heritage with watches, Cartier spearheaded the design of the modern timepiece. It did this through a play with shapes, jewellery setting techniques and achieving harmony between bracelet and case. Signature elements that continue to live on in Cartier’s watches today.

Cartier the beginnings

In 1847 Paris, Louis-François Cartier bought the workshop where he was apprenticing under master watchmaker Adolphe Picard. The 28-year-old had ambitions to grow the modest business and turned his focus to dealing in jewellery. Against the backdrop of revolutions and the Second French Empire, he concentrated on sourcing only the finest pieces. From 1856, Princess Mathilde (niece to Napoleon) became an important early patron. She purchased more than 200 jewels over the course of her lifetime. By 1870, at the dawn of the French Third Republic, son Alfred Cartier had joined his father, and in 1874 took over running the firm.

A brilliant businessman, Alfred transformed the company from buying and selling to designing and manufacturing. Eventually he established the Paris showroom in the Rue de la Paix, in 1899. This move prompted other jewellers to set up shop – transforming the street into the most important jewellery district in Paris. Conscious of his growing competition. Alfred set the ambitious goal of expanding Cartier to other major cities outside of France. He handed the business over to his three sons. Each capable in his own right. The combination of these three brothers – Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier – would prove to be a tour de force.

Enter Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier

Before 1900, Cartier jewellery reflected the times, meaning eclecticism. Louis, a brilliant visionary who joined his father in 1898 however, pioneered the use of platinum. He developed a lacework technique that allowed for very flexible, almost invisible settings. Stronger and lighter than both gold and silver, the “Garland Style” revolutionised the industry. It captivated crowned heads from around the world visiting Paris for international exhibitions. Thereafter, Pierre, and later Jacques, ventured abroad to conquer new territories. In charge of Paris, Louis drew inspiration from the cultures his brothers explored. His insistence on perfection proved key to their overseas expansion.

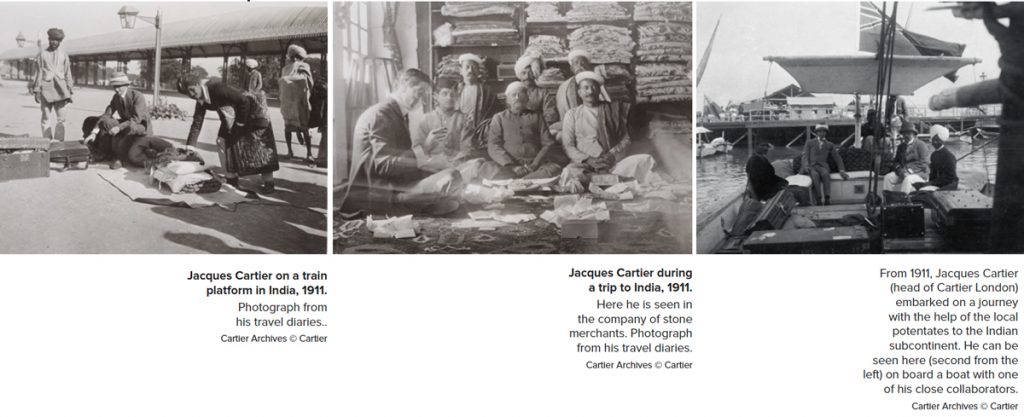

Encouraged by King Edward VII, Pierre established the London branch in 1902. (The flagship New Bond Street boutique opening in 1909.) He repeated the entrepreneurial process across the Atlantic in New York in 1909. Allowing the brand to deal directly with America’s new-money millionaires. Less than a decade later, he secured Cartier’s third flagship boutique in 1917. Famously exchanging a pearl necklace and $100 for the brand’s now iconic 5th Avenue premises. In between, Pierre also made trips to Russia starting in 1904. Jacques, who took over the London branch in 1906, discovered the “Jewel in the British Crown” in the Maharajahs visiting from India. In 1911 he travelled to the subcontinent.

‘Never copy, only create’

The new, opulent frontiers had a major impact on the Cartier style. Louis and his designers were among the first to pair daring colours, such as blue and green, with abstract geometry – predating the Art Deco movement. Then in an about-turn, Cartier reinterpreted floral motifs of traditional Indian jewellery. Leaves, flowers and berries in never-before-seen colour combinations: red, green and blue. ‘Foliage’ or ‘Hindu’ jewellery (referred to as Tutti Frutti from the 1970s onwards) broke with Art Deco fashion. It sparked a craze around the globe. Two of the world’s best-dressed ladies, Lady Mountbatten and Daisy Fellows were proponents of the style.

It was this period of heightened creativity that birthed the modern wristwatch. Since joining the firm, Louis had developed Cartier’s own line of unique pocket watches. In 1904, he devised a prototype watch for Brazilian pilot Alberto Santos-Dumont. It was the first to integrate bracelet attachment horns into the case – allowing for wearing on the wrist. The idea proved popular and made Cartier the forerunner to an emerging new style of horology. Drawing on his avant-garde approach to jewellery, Louis’ watch designs were ahead of their time. Specifically, his use of shapes set Cartier apart from other watchmakers.

Cartier Shapes

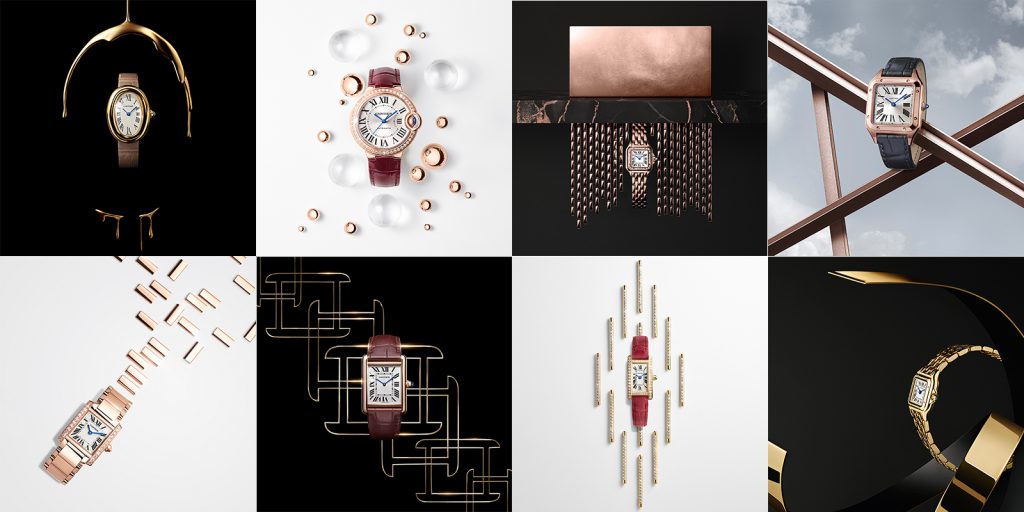

Several of Louis’ pocket watches had not been round. The Santos was derived from a square shaped model with round angles. (The design was finalised in 1910 and launched in 1911.) Louis’ interest in “Shaped watches” only grew. The prototype was followed by the Tonneau, Tortue and Tank shapes in 1906, 1912 and 1917 respectively. The latter, inspired by press pictures of the first army tanks, was particularly important. Its two parallel lines formed the purest shape possible for a wristwatch. The Tank, going into production from 1919, became a legend. The strength of its shape saw several variants evolve.

Cartier’s tradition of shape play continued over the 20th Century, adding to the Maison’s list of signature timepieces. These include: the 1957 Baignoire (French for ‘bathtub’), stemming from a 1912 oval-shape design by Louis; the 1967 Crash, inspired by a deformed Baignoire Allongée brought back to the repair department in London; the square-shaped Panthère launched in 1983; the 1985 Pasha, a round shape among Cartier’s rectangles and ovals; the 2007 pebble-shaped Ballon Bleu; and the 2016 Hypnose, also inspired by the 1912 oval-shape model. Throughout, subtle and extravagant measures preserved the master jeweller’s identity.

Beyond The Case

Cartier’s jewellery background gave its watches a distinctive flavour. A sapphire cabochon on the crown – from the Santos design – became a recurring hallmark. Louis was quick to combine the two facets of the atelier. His 1914 Panther Pattern wristwatch debuted what would become the Maison’s most enduring motif. (Championed by Jeanne Toussaint.) This eventually led Cartier to develop a “fur” setting, emulating the texture of the big cat with precious jewels. Other settings such as “Pave” and “Channel” were also prominently featured. In fact, offering a jewellery version of each watch became the norm. Some women’s models being extraordinarily sumptuous.

Cartier’s knowledge of jewellery carried over to the wrist component of a timepiece. In 1910, Louis conceived yet another innovation. Based on jewellery clasps, the déployant allowed for an array of metal bracelets in both men’s and lady’s watches. Notable bracelets include: the 1978 “Santos”, with screws in the lugs to match the original Santos bezel; the 1983 “Panthère”, reintroduced for women in single, double and triple loops (and cufflinks); and the newly released “Maillon” with offset links. Tutti Frutti and other jewellery styles were also combined into bracelet watches. Preserved today in Cartier’s High Jewellery watches, the ‘Cartier watch’ lives on!

Cartier 2020 creations: Pasha, Métiers d’Art

Returning in 2020, the Pasha exemplifies Cartier’s code for watch design. Its dial design places a square inside a circle. Its crown and fluted crown cover house matching blue sapphires. Available in steel, gold or leather, the interchangeable strap achieves harmony with the round case. A sapphire crystal case back reveals an in-house movement – the 1847 MC automatic calibre – resistant to both magnetism and water. In addition to steel, 35mm and 41mm case sizes are available in 18K pink and yellow gold respectively. 35mm jewellery versions exist in 18K pink and white gold. As well as 41mm skeletonised versions in steel, 18K pink gold, and 18K white gold with diamond-set bezel.

Likewise, two new “Métiers d’Art” watches demonstrate Cartier’s application of jewellery techniques to watchmaking. The first combines gold work with the composition art of marquetry. Yellow gold wires are embedded in natural straw elements to produce 75 blades in 11 different colours. The panther motif continues in the second creation, which adapts the filigree technique to be used with enamel. Fixed with tiny strands of yellow gold, the stretched glass takes on the form of bamboo. Between the stalks prowls the big cat. The fur setting of her coat is complimented by brilliant-cut diamonds encrusting the bezel. Available in 42mm and 36mm diameters respectively. (Both 18K white gold watches are limited to 30 pieces each.)

The incredible spirit of ingenuity and innovation continues to be imbued in each and every Cartier creation. Guided by its rich history and pioneering founders, it’s clear the Maison has its sights firmly set on the future. And we cannot wait to see what comes next.

Rolex

Rolex A. Lange & Söhne

A. Lange & Söhne Blancpain

Blancpain Breguet

Breguet Breitling

Breitling Cartier

Cartier Hublot

Hublot Vacheron Constantin

Vacheron Constantin IWC Schaffhausen

IWC Schaffhausen Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre OMEGA

OMEGA Panerai

Panerai Roger Dubuis

Roger Dubuis TAG Heuer

TAG Heuer Tudor

Tudor FOPE

FOPE Agresti

Agresti L’Épée 1839

L’Épée 1839